McDermott has taught for 62 years.

McDermott has taught for 62 years.

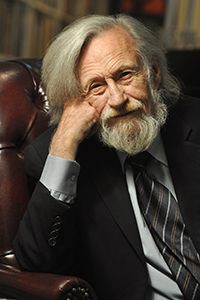

On a Tuesday this April, John J. McDermott greets me from his seat on a bench outside of Nagle Hall. He is six weeks into his convalescence after a quadruple spinal laminectomy. And yet, McDermott, who holds the Melbern G. Glasscock Chair in the Humanities and has held the George T. and Gladys H. Abell Professorship in Liberal Arts, is surprisingly not prone; he is already walking around campus with his plain leather satchel (an antique physician’s bag that was a gift from students) and signature fedora. In fact, the 82-year-old University Distinguished Professor of philosophy has returned to teaching much ahead of schedule and despite his doctor’s wishes. This bench is a temporary resting spot, like several others along the way to the Academic Building, where he teaches American Philosophy.

As we enter the Academic Building, the centerpiece of main campus, McDermott laments that he lost a battle with university administrators to preserve the building’s original palladium doors and windows during a renovation in the early 1980s. When he started teaching at Texas A&M at age 45, he recalls that he would take the stairs “two up, four down.” Now, with nearly four decades of surplus wisdom, he chooses to take the elevator.

In the classroom, students hush upon McDermott’s entrance. Unlike many other college students, his are not distracted by laptops or cellphones. Pens poised over paper, they are focused, eager to hear what stories he will share today. It would seem anachronistic with any other professor, but with McDermott at the helm, it is fitting. Then, just as they expect, he calls roll to check attendance, his voice low and gravelly, a New York accent still prominent.

McDermott’s class is a tapestry woven of various tales. For the next 90 minutes, he regales the group with stories about his children, personal details about American philosophers William James and John Dewey and advice on traversing through the journey of life. His lesson is interspersed with sage one-liners—“education is supposed to be a feast, not an obstacle course”—and punctuated by his occasional chalkboard scribblings.

The Nectar is in the Journey

McDermott grew up in Depression-era New York City, the oldest of eight children in a lower middle-class Irish Catholic family. They had no books, but they were, as McDermott describes, “rich in stories and experiences.”

For 62 years, the professor has been at the front of a classroom. He has taught preschool children, high schoolers, disabled students, prisoners, and, of course, college students. In that time, his beard and wild shock of hair have grayed, but his teaching philosophy has remained mostly unchanged.

“I believe that everybody’s educable,” McDermott said of his calling. “I live the life that I teach, and I teach the life that I live.”

Evidence of this mantra can be found in nearly all of McDermott’s writings. The stories he tells are like onions— peel back one layer and another stratum of meaning is revealed.

In one of his tales, McDermott recalls his time as a 16-year-old volunteer for the Catholic Worker Movement in New York City at a triage ward at the Bellevue Hospital. A quadruple amputee requested two Puerto Rican cigars; no other cigars would suffice. After a frenzied search, McDermott produced the cigars. Many years later, he wrote that he finally understood the meaning of this experience: “I was teaching the philosophy of Albert Camus, and the theme was personal authenticity. In a flashback, my Puerto Rican patient taught me of authenticity, the aesthetic moment, and the difference between the literal and the symbolic.”

McDermott instills in his students his belief that one can grow from every experience; and he does so not only through words, but also through deeds. His post-surgery trek across campus is evidence that he practices what he preaches: By continuing to do what he loves most, undeterred by all obstacles, he is encouraging students to savor their every experience, despite discomfort or challenge.

“I live a service life,” he added. “We’re here to serve the state, nation and the world at large by teaching, research and service. Because we are a land grant university, this is especially so.

“I want my students to come alive to themselves and buy into the importance of their own experiences. With the saturation of modern technology, I find my students to be increasingly disconnected from their own experiences. The affective is being squashed. These experiences have to be cradled, reconnoitered and reconstructed.”

In a course on the philosophy of aesthetics, which McDermott has taught for 50 years, he requests that students create, perform or build something they have never done before and write about the experience. Students have worked with clay, painted, written poetry, danced the tango and even given up certain personal comforts for the duration of the project. This opportunity, McDermott believes, allows them to reflect on their experiences in a deeply personal way.

Alex Haitos, McDermott’s research assistant and a third-year doctoral student in the Department of Philosophy, believes that this authenticity and unique teaching style resonates with McDermott’s students. “He doesn’t simply exposit the text,” said Haitos. “He wants you to understand ideas by connecting them to your own life and experiences.” On a weekly basis, McDermott receives correspondence from former students thanking him for the contributions he made to their lives. You don’t need to know him long to recognize his inspiring dedication and selflessness. Charles Carlson, who received his doctorate in philosophy last year and worked for five years as his research assistant, said McDermott’s influence on others extends far past his students. “The number of people he helps is amazing,” said Carlson. “For him, it’s a way of life. The guy who fixes his boots, the dry cleaners, and the people who bag his groceries all know him by name and as someone who cares about them.”

Still, after teaching tens of thousands of students, McDermott claims he is the one who has gained the most. “From my students, I can say that I have learned far more than I have taught. And what did I learn? Life is difficult.”

Reflection is Native and Constant

McDermott doesn’t practice meditation—at least, he doesn’t attempt to free his mind of thought. “You should always be reflecting,” he explained. “Following John Dewey, reflection is native and constant.”

His constant search for truth and progress is apparent in his 37-year tenure at Texas A&M. He is contemplative about his professional journey and the way the university has changed over time: “A&M has a pockmarked and splendiferous history,” he said. Furthermore, in his tireless efforts to give voice to faculty opinions, McDermott is a catalyst for reflection for the university as a whole.

In 1983, he called the first faculty meeting in the history of Texas A&M. That meeting, held in Rudder Theater, was the seed that grew into the Faculty Senate. For McDermott, this was “a revolution in consciousness” for the university.

That same year, he became the charter speaker of the Faculty Senate and continued in that role for three years. Today, the Senate is one of the university’s primary governing bodies, responsible for reviewing all policies related to curricula and instruction, admission, scholarships and faculty hiring.

McDermott’s contributions to Texas A&M continue. In an effort to reconnect retired faculty with the university, he became the founding director of the Community of Faculty Retirees in 2012.

“In the old Webster’s dictionary—the 19th century one that I can’t pick up any more—you look up ‘retirement,’ and one of the meanings is ‘forgotten, abandoned,’ ” McDermott explained. The Community of Faculty Retirees is his preemptive strike to prevent faculty from fading away.

The group hosts speakers of all backgrounds, including a recent presentation by Celia Sandys, the granddaughter of Winston Churchill, and guest lectures by former faculty.

“I’m ecstatic about the wonderful response from retirees and the cooperation from the university,” said McDermott about the events, which typically draw 50 to 100 faculty retirees. “There are smiles upon smiles at every gathering.”

I want my students to come alive to themselves and buy into the importance of their own experiences.

- John J. McDermott

Another marker of McDermott’s foot hold at Texas A&M is being the third person to receive the title of University Distinguished Professor in 1982 (there are now more than 120). The honor is reserved for pre-eminent faculty members who have generated a sea change in their field. For McDermott, this was giving new life to a “mocked and dismissed area of philosophy.” His work on the 19-volume Harvard critical edition of The Works of William James is one way we “brought American philosophy to the center of the stage.” Following the completion of that project, McDermott took on the role of editor, project director and principal investigator for the 12-volume edition of The Correspondence of William James. He worked on the collection for more than a decade; the final volume was published in 2004.

Eat your Experiences

In his book The Drama of Possibility, McDermott wrote, “The most perilous threat to human life is second handedness, living out the bequest of our parents, siblings, relatives, teachers, and other dispensers of already program med possibilities.” This idea of “second handedness” fuels McDermott’s personal motto: “Eat your experiences.”

McDermott’s teachings transcend the boundary of the classroom. His lifelong quest is to teach people to be trailblazers, freethinkers and explorers of their passions. As Carlson puts it, “He’s not necessarily preparing philosophers, he’s helping people become confident in what they’re doing to develop and nurture their interests.”

This out-of-the-classroom experience culminates each year with a reception at his home. McDermott and his wife Patricia host all of his students for a celebratory gathering at which McDermott learns more about his students and give them the opportunity to explore his impressive library.

Indeed, McDermott has taken his own advice on savoring experiences. Sharing and passion are his way of life. He was the first in his family to go to college. He left his home state of New York to create new roots in Texas. He was a founding member of the American Montessori Society and a charter member of the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy. Four academic conferences have been held in his honor. His 50-plus-page curriculum vitae lists published work, awards and achievements. He has been married to Patricia for 24 years, and he has five children (all, as he describes them, in a “helping profession”) and six grandchildren.

Cherished Apples

As I tried to encapsulate the depth and breadth of McDermott’s experiences into a mere 2,000 words, the poem “After Apple-Picking” by Robert Frost came to mind. During our interviews, McDermott would share poems that inspired him. Knowing his love for the written word, I sent him a stanza that reminded me of the legacy he has created: “There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch, Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall.”

McDermott responded with two sentences: “I am my stories, their happening, their telling and retelling, their adumbrations and their messaging. Along with Robert Frost and his ‘fallen apples,’ I believe that the nectar is in the journey and there alone.”

With tobacco still lingering in his pipe, McDermott’s journey is far from complete. There are far too many more apples to pick before he sleeps.

By Monika Blackwell

This article was originally published in the summer 2014 issue of Spirit magazine. Read the full publication.

Texas A&M Foundation

The Texas A&M Foundation is a nonprofit organization that solicits and manages investments in academics and leadership programs to enhance Texas A&M’s capability to be among the best universities.

You can support faculty and students in the College of Liberal Arts with a gift of an endowment to the Texas A&M Foundation. For additional information or to learn more about scholarships, research and program-focused giving to the College of Liberal Arts, contact Larry Walker ’97 with the Foundation at (800) 392-3310, (979) 845-5192 or lwalker@txamfoundation.com.