Common Earthquake Myths

Can animals sense earthquakes ahead of humans?

Animals can feel earthquakes just as we can, and it is highly likely they have a more acute sensitivity to the ground shaking than we do. They may sense smaller earthquakes happening that we don’t notice, which sometimes could allow them to display unusual behavior prior to a major earthquake. However, we prefer to use more reliable and quantifiable data from seismic networks and space-based systems that measure ground motion in order to inform earthquake forecasting.

Are earthquakes more likely to occur in certain types of weather or during certain times of the year?

There’s really no season for earthquakes like there is for hurricanes and tornadoes. Things like the gravitational pull of the moon or seismic vibrations of the Earth can trigger a fault to slip and cause a quake, but these factors play very minor roles. The best predictor of an earthquake is another earthquake, so if you experience one, be prepared for another one that is likely to follow.

Could California fall into the sea during a massive earthquake?

No. While a fault is like a giant crack, one will never open up and allow California to fall into the sea during an earthquake. That’s not to say that there wouldn’t be any landslides that cause coastal properties to slip into the ocean, but the pressure of the Earth’s plates pushes the fault together, keeping California connected to the rest of the United States.

Are earthquakes around the world becoming more frequent?

In the long term, no. Random events, however, can cluster together in space and time and make it seem so. The truth is that with an increase in built environment and human population, we are more susceptible to earthquake hazards; therefore, we hear more news about earthquakes, which may give the appearance that they are becoming more frequent.

How many earthquakes occur around the world annually?

Zillions. Although we only really notice the big ones, tiny earthquakes are constantly occurring beneath the Earth’s surface.

At what magnitude are earthquakes likely to cause major damage?

While we are mostly concerned with magnitude 6 and larger earthquakes, magnitude 4’s and 5’s and even 3’s can cause significant damage if they occur in an urban area, as proximity to the quake is another major factor.

Can scientists predict earthquakes?

Predicting earthquakes is similar to weather forecasting. For example, the Southern California Earthquake Center has developed technology that allows us to determine the probability of earthquakes in certain areas thanks to geologic studies of the 1,000-years history of faults and using mechanical-based models to establish earthquake probability over various time intervals. We know that some sections of the San Andreas fault have a very high probability of producing another large earthquake in the next 30 years. There are many other faults in California and around the country, however, that we don’t know as much about. These are difficult to forecast but could rupture at any time.

What is one of your most memorable discoveries from your career?

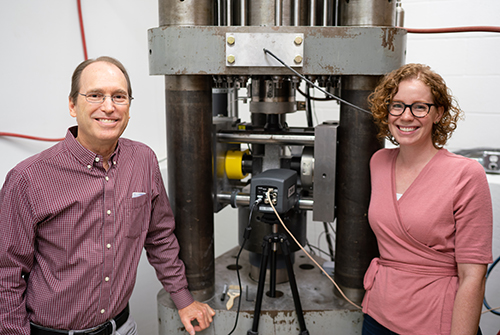

Dr. Chester operates machinery in the geosciences lab with the help of graduate students like Monica Barbery '19 to better understand the mechanics of earthquakes.

Dr. Chester operates machinery in the geosciences lab with the help of graduate students like Monica Barbery '19 to better understand the mechanics of earthquakes.

I’ve had the chance to work with some incredible individuals on many memorable projects during my career. One of my favorite moments, however, occurred during an ocean-drilling expedition that I co-led after the Tohoku disaster, which occurred when a magnitude 9 earthquake caused a tsunami to strike Japan on March 11, 2011. I spent two months aboard a ship off the coast of Japan one year after the quake, where I worked closely with other researchers and a drilling team to examine the strength of the Tohoku fault when it slipped. After studying drill-core samples and analyzing our temperature-measurement data, we found that the fault was indeed incredibly weak during the earthquake, which is the first time that has ever been proven. On top of the remarkable moment when we recovered a core sample of the fault, we also witnessed a perfect annular eclipse from the deck of the ship that very same morning!

How has the David Bullock Chair benefited you and your research?

Holding the David Bullock Chair in Geology has helped me tremendously! The annual stipend from the chair helps us run our laboratory and teach the courses that require the use of our rock-deformation machines, which can cost us $200 to $300 per use. Funds also help us execute senior capstone design projects, on which we collaborate with mechanical engineering students, and enable us to advance our facilities so that they remain some of the best in the nation. Moreover, funds allow us to develop new methods for researching the most challenging questions in our field.

To learn more about how you can support the College of Geosciences and research like Dr. Chester’s, contact Gary Reynolds ’88 at greynolds@txamfoundation.com or (979) 862-4944.